Merle Hoffman

Founder/President, Choices Women’s Medical Center

November brought an early holiday gift. I was delighted to hear from a friend of many years, Edna Adan Ismail, whose work in Somaliland assisting women has inspired people around the world. She and I were able to speak on a ZOOM call about her experiences, and, especially in these difficult times, I want to share her inspiring example.

I wanted her to talk about the initial catalyst for her mission and vision for women’s healthcare. This is a commitment started in 1950 when she was 13 years old accompanying her famous father, Dr. Adan Ismail, on his rounds to treat patients at the 40-bed hospital in Erigavo, British Somaliland. He instructed her how to feed weak children, wash syringes and sterilize instruments and had her oversee his patients when, as the physician in charge of health services for the entire region, he had to drive long distances to other hospitals and cities.

Edna adored him and admired his generosity, hard work and passion for caring for the sick. She said his example of selfless service planted a seed in her heart to do her work with love and determination, despite the challenges. As she spoke, I recalled the importance of role models in my own life, having known a physician whose selfless service to patients influenced my values.

Edna went on to discuss her efforts to improve women’s health, especially reducing the high maternal mortality rate that Somaliland had. She began the first prenatal and first women’s clinic in the hospital in Hargeisa in Somaliland in 1961 where she trained midwives. One of her challenges from the very beginning was to gain the trust and respect of women in Somaliland, including traditional midwives who had no medical training and were suspect of what she said and did to help women in childbirth and pregnancy generally.

The traditional midwives grew to respect me, she said, when they saw that she could do things and help their patients in ways they couldn’t. And she was always respectful of them, thanking them for their help and for calling her when they knew women were having trouble giving birth. She also invited them to the hospital where “we could learn from each other.” She was horrified when she learned that if a woman in childbirth was bleeding out, they would chant or make a prayer. But her “lessons” of basic maternal care and cleanliness were not lost on the midwives.

The battle to end female circumcision (also known as Female Genital Mutilation, or FGM) has been the most challenging work of her life. She recalled attending a WHO Congress on Obstetrics and Gynecology in Khartoum, Sudan in 1976 where she heard FGM discussed openly, in an audience of both men and women, for the first time. She had not realized before how widespread the procedure was that had been forced on her as an 8-year-old child by her mother and village women, and that she saw the effects daily on women in her maternity wards.

When she returned home to Somaliland, Edna and her team began providing training to midwives, nurses and doctors that included courses on the negative effects of FGM. She has also tried to involve fathers and religious leaders in the campaign against it. In 2018, Somaliland became the only country in the world with a fatwa (Islamic religious ruling) against infibulation (FGM).

Edna had dreamed for a long time of building and operating a hospital in Somaliland that would be a leader in maternal and child health in her country. She described the collective effort that went into the project, and how her own work in patient care influenced the hospital’s design and operation.

The Edna Aden Maternity Hospital in Hargeisa opened in 2002 and is acclaimed for its teaching program and high level of patient care. Over four thousand health workers have been trained, comprising 80 percent of the health workers in Somaliland. Edna successfully achieved her goal of training 1,000 midwives for Somaliland. She said that over 35,000 women have been served by her hospital, resulting in a maternal mortality rate for her country of 237 per 100,000, which she acknowledged was not ideal but an improvement from the previous rate of 1,600 per 100,000 in 2000 before she opened her hospital.

She is also grateful for the international support she has received, and the stability of her country which has encouraged people to come and assist her. She thanked the Friends of Edna Hospital Charity for their 24-year-long support.

In concluding our discussion, I asked her how she saw the women’s health struggle today – in Somaliland and internationally. She said that education for girls was a critical issue to train women to make decisions for themselves, to think for themselves, and to give them courage to work together to solve problems. Edna is very proud of her former trainees who now hold important positions with international organizations, proving her conviction that education is the best gift that one can give to a girl or woman.

In accomplishing this, Edna Adan is an example for everyone, and I am proud to know her.

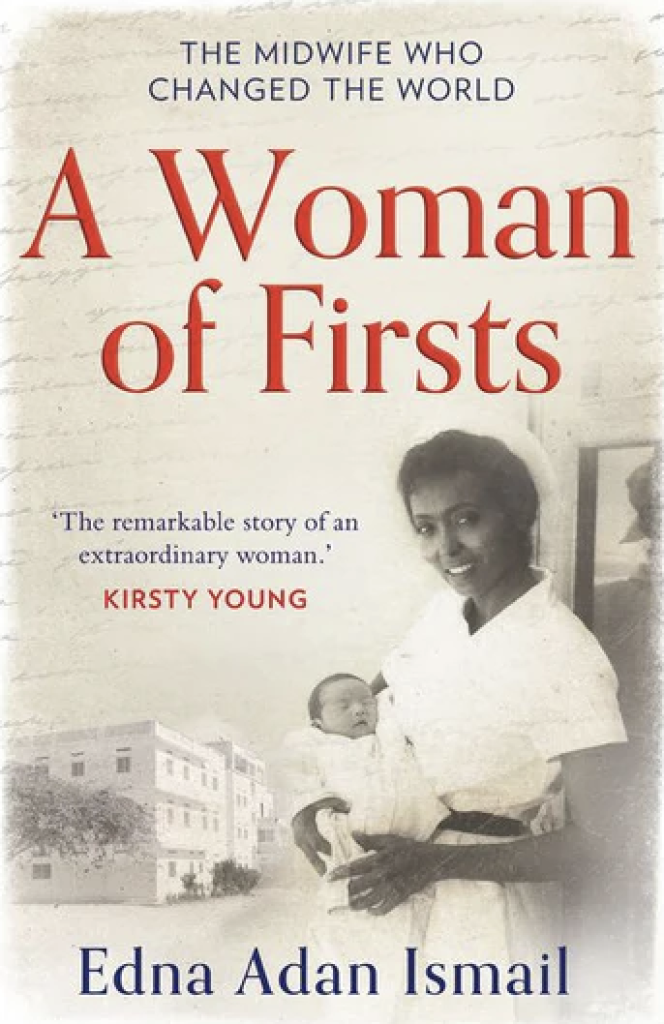

We encourage you to read her autobiography:

“A Woman of Firsts”

Edna Adan Ismail

“The remarkable story of an extraordinary woman”